Most frogs reproduce by laying eggs. In most frog species, the eggs will hatch into tadpoles, but this isn’t always the case. Some species do not have a tadpole stage.

Most frogs start their lives as aquatic tadpoles, which transform into adult frogs over time. However, some frog species do not start as tadpoles. They either lay eggs that hatch into fully developed frogs, or retain the eggs inside of their bodies and give birth to fully developed young.

There are over 7,000 frog species worldwide, found on every continent, excluding Antarctica. With this wide distribution, they live in a very wide range of habitats, from rainforests to mountainous areas, to dry regions.

Different frog species have adapted to their environments and developed breeding methods that are practical for the areas they live in.

Most Frogs Start Their Lives as Tadpoles

Most frog species lay eggs in shallow, fishless, freshwater bodies.

This could be in fishless ponds, seasonal pools, temporary rain puddles, flooded ditches, lake edges, river backwaters, bogs, marshes, swamps, slow-flowing streams, and even in deep tire tracks or potholes filled with rainwater.

Some frog species such as the red-eyed tree frog lay their eggs on leaves hanging over water – and other species lay their eggs in foam nests built over, or at the edge of water bodies.

Many tree frog species lay their eggs in puddles that collect in the holes of trees, or water-holding plants such as bromeliad plants and other water-filled crevices in the forest canopy.

A few weeks days, to a few weeks, tiny tadpoles will hatch from these eggs.

Tadpoles are very different from adult tree frogs because they have features highly adapted for their aquatic life. They have external gills which they use to breathe underwater, just like fish – and also have a flat fin-like tail to help the swim.

After a few weeks, to a few years (depending on the species) these tadpoles will go through a process known as metamorphosis and transform into miniature frogs.

During this process;

- Their gills are covered by a special pocket of skin and are eventually lost

- Their lungs enlarge and develop further

- The tail shortens and is eventually absorbed into the body

- They grow legs strong legs for moving on land

Once metamorphosis fully is complete, the tadpoles are now young frogs and will leave the water for a mostly terrestrial, or semi-aquatic life (depending on the species).

Some Frogs Lay Eggs Which Hatch Into Froglets

Many frog species evolved to live in environments with low availability of undisturbed surface water suitable for tadpoles to live in. For this reason, they eliminated the tadpole stage from their life history.

These frogs lay eggs which then hatch into young fully developed frogs which are morphologically similar to the adults. This is known as ‘direct development.’

The eggs are usually laid in protected terrestrial environments which could be; on leaves, in tree hollows, in caves, under logs in damp soil or leaf litter, and even in abandoned bird nests.

As a general rule, frog eggs require moisture to develop and hatch successfully.

For this reason, frogs that lay their eggs away from the water usually lay them in damp locations, or provide moisture for the eggs by brooding them.

In many species, the males or females (or both) will remain with the eggs to guard them from predators.

Here Is a Table That Shows Where 15 Direct-Developing Frog Species Will Lay Their Eggs

Frog Species |

Scientific Name |

Where They Lay Their Eggs |

| Common coquí | Eleutherodactylus coqui | In tree holes, on the leaves of terrestrial trees or plants, and in abandoned bird nests |

| Red-eyed coqui | Eleutherodactylus antillensis | In damp leaf litter or soil |

| Bush squeaker | Arthroleptis wahlbergii | In damp leaf litter |

| Common squeaker | Arthroleptis stenodactylus | In hollows or burrows in damp soil |

| Rio Grande chirping frog | Eleutherodactylus cystignathoides | In damp soil |

| Variable bush frog | Raorchestes akroparallagi | On the upper side of large leaves |

| Counou robber frog | Eleutherodactylus counouspeus | In caves |

| Common tink frog | Diasporus diastema | In bromeliads |

| N/A | Adelophryne maranguapensis | In bromeliads |

| Mozart’s frog | Eleutherodactylus amadeus | Under logs, rocks, and other objects on the ground |

| N/A | Leptodactylodon ovatus | In holes and cracks in rocks |

| Cusco Andes frog | Bryophryne cophites | In nests of moss |

| Grand Cafe robber frog | Eleutherodactylus pinchoni | In damp soil, or in bromeliads |

| Neiba whistling frog | Eleutherodactylus parabates | In damp soil |

| Cuban bromeliad frog | Eleutherodactylus varians | In bromeliads |

Other direct-developing frogs include:

- All frogs of the genus Arthroleptis (49 species)

- All frogs of the genus Diasporus (16 species),

- All frogs of the genus, Adelophryne (12 species),

- All frogs of the genus Phyzelaphryne (2 species)

- All frogs of the genus Pseudophilautus (80 species)

- All frogs of the genus Raorchestes (73 species)

- All frogs of the genus Eleutherodactylus except for the Golden coquí E. jasperi (199 species)

The eggs of direct-developing frogs are usually extra large because they have a lot of yolk to compensate for the lack of feeding as a tadpole.

The yolk will remain attached to the intestine to nourish the froglets for the first few days after hatching, in a process similar to chickens.

Such reproductive behavior allows these frogs to live in forests, mountains, and even in urban areas – without the limitation of a direct dependency on water.

Some Frogs Give Birth To Live Young

A few frog species such as the Golden coquí (Eleutherodactylus jasperi) do not lay eggs at all – instead, they give ‘birth’ to live young.

When these frogs mate, their eggs are fertilized internally and are retained within a uterus formed of fused portions of the oviducts.

The developing embryos are nourished by the egg yolks, and after a few weeks, the female will give ‘birth’ to tiny, fully metamorphosed froglets. This is known as “Ovoviviparity.”

Other ovoviviparous frogs include:

- Broad-headed rainfrog (Craugastor laticeps)

- Robust forest toad (Nectophrynoides viviparus)

- Kihansi spray toad (Nectophrynoides asperginis)

- Pseudo forest toad (Nectophrynoides pseudotornieri)

- Frontier forest toad (Nectophrynoides frontierei)

- Smooth forest toad (Nectophrynoides laevis)

- Minute tree toad (Nectophrynoides minutus)

- Tornier’s Tree Toad (Nectophrynoides tornieri)

- Morogoro tree toad (Nectophrynoides viviparus)

- Uzungwe Scarp tree toad (Nectophrynoides wendyae)

- Vestergaard’s forest toad (Nectophrynoides vestergaardi)

- Wide-headed viviparous toad (Nectophrynoides laticeps)

Since these frogs give birth to live young, they do not have a tadpole stage.

Darwin’s Frogs Brood Tadpoles in Their Vocal Sacs

Darwin’s frogs (Rhinoderma darwinii), are found in the forests of Chile and Argentina. These frogs have unique reproductive behavior in which they ‘swallow’ their tadpoles, and release them as fully metamorphosed froglets.

Female Darwin’s frogs lay there in moist leaf litter. The males, then fertilize the eggs externally and remain nearby.

Once the embryos have developed to a stage whey they can wriggle inside of their eggs (about 20 days after the eggs are laid), the males swallow the embryos and put them in their specialized vocal sacs – where they hatch in about 3 days.

After hatching, the tadpoles will develop within the vocal sack for about 50 – 70 days. They are nourished by absorbing paternal nutrition produced by the wall of the sac, via the skin, and yolk from the egg.

As they develop, they will be able to consume parental nutritious secretions via the mouth and absorb them through their digestive system.

When the tadpoles have completed metamorphosis and transformed into miniature frogs, they will move from the male’s vocal sack, and hop out of the mouth.

Surinam Toads ‘Give Birth’ Out of Their Back

Surinam Toads are a fully aquatic frog species from the northern Amazon basin of South America. These toads are unique, in that the female gives “birth” to the young out of her back!

The female releases about 100 eggs during mating. Next, the male fertilizes the eggs and pushes them into the female’s back – and the skin of the female then encloses the eggs

The embryos will develop to the tadpole stage inside of their egg pockets but will remain until they complete their development and become toadlets in about three to four months.

Once the eggs hatch, fully formed toads will pop out of the female’s back.

Having a Tadpole Stage Has Disadvantages

The tadpole stage is the most vulnerable stage of most frogs’ lives. Frogs often lay eggs in temporary pools of water, and sometimes, these pools dry up before the tadpoles have had enough time to metamorph into adults.

Also, its common for many frogs lay eggs in the same pools, and when the eggs hatch, the pool will be crowded. This means the tadpoles have to compete for space and other limited resources.

Overcrowding often leads to cannibalism in which large tadpoles eat small, vulnerable tadpoles. For example, large cane toad tadpoles have been documented eating smaller tadpoles of their own species.

Tadpoles are also preyed on by fish, adult frogs and toads, salamanders, newts, birds, snakes and other reptiles, many mammals, and even predatory insects such as water boatmen and dragonfly larvae.

For these reasons, it’s common for over 90% of tadpoles in a pond to be wiped out before they can undergo metamorphosis and transform into adult frogs.

Common Questions About Frog Development

What Frogs Don’t Start as Tadpoles? All frogs of the genus Eleutherodactylus, which includes the Common coquí, the Rio Grande chirping frog, and 198 other species do not start as tadpoles. They lay eggs that hatch into miniature frogs, bypassing the tadpole stage. This reproductive behavior is known as ‘direct development’.

Do Bullfrogs Start as Tadpoles? Bullfrogs lay eggs in shallow bodies of fresh water, which hatch into tadpoles. In some species such as the African bullfrog (Pyxicephalus adspersus), the males remain with their tadpoles to protect them from predators, and will also occasionally create paths for the tadpoles to escape drying ponds.

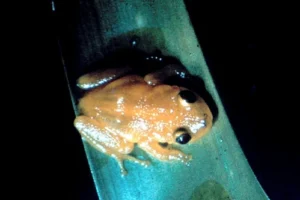

Photo credit: Magnus Hagdorn (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Sources:

Sarah E Westrick, Mara Laslo, Eva K Fischer (2022) The Natural History of Model Organisms: The big potential of the small frog Eleutherodactylus coqui eLife 11:e73401 https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.73401

Elinson, Richard. (2001). Direct development: An alternative way to make a frog. Genesis (New York, N.Y. : 2000). 29. 91-5. 10.1002/1526-968X(200102)29:23.0.CO;2-6.

AmphibiaWeb (2020) Eleutherodactylus jasperi: Puerto Rican Golden Frog. University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA.

Hedges, S. B.; Duellman, W. E. & Heinicke, M. P. (2008). “New World direct-developing frogs (Anura: Terrarana): Molecular phylogeny, classification, biogeography, and conservation” (PDF).

AmphibiaWeb 2016 Rhinoderma darwinii: Darwin’s Frog. University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA.

Fuentes-Navarrete, Marina & Gomez-Uchida, Daniel & Canales-Aguirre, Cristian & Galleguillos, Ricardo & Ortiz, Juan. (2014). Development of microsatellites for Southern Darwin’s frog Rhinoderma darwinii (Dumeril & Bibron, 1841). Conservation Genetics Resources. 10.1007/s12686-014-0279-4.

Calef, G.W. (1973), Natural Mortality of Tadpoles in a Population of Rana Aurora. Ecology, 54: 741-758. https://doi.org/10.2307/1935670