Frogs are intriguing creatures that attract the curiosity of many people. Many species also tend to be very secretive, so they are not frequently encountered most times of the year. Because of this, there are many misconceptions about these animals.

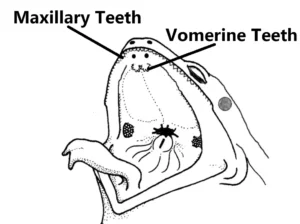

Most frog species have tiny teeth around the edge of the jaw, known as Maxillary Teeth – and also have teeth on the roof of their mouth known as Vomerine Teeth. Frogs generally do not have teeth on their lower jaw. Only one out of more than 7,500 known frog species has true teeth on its lower jaw.

While we have teeth dedicated to specific functions (such as canines to rip apart food, incisors to bite, and molars to grind), frogs do not. Their teeth are fairly uniform and do not specialize.

The function of a frog’s teeth is not to chew, but to hold prey and keep it in place as the frog swallows it alive and whole.

The Tadpoles of Many Frog Species Have “Beaks”

Most frog species start their lives as fully aquatic tadpoles. Tadpoles in their early stage of development are almost completely herbivorous and eat algae, phytoplankton, and detritus.

Tadpoles have a pair of upper and lower jaw sheaths at the margins of their mouth, which together form what is sometimes called the tadpole “beak”. They also have several rows of denticles (labial teeth) outside the jaw sheaths.

Tadpoles use their beak and denticles to scrape off the algae that grow on plants, rocks, or at the surface of the water.

The denticles are not made of bone and enamel like our teeth are, but of keratin — a protein substance that, for instance, also makes up our fingernails and hair.

Tadpoles also have little or no tongue-like tissue and will eat by sucking the food into their throat and the food enters the long intestine where it is digested.

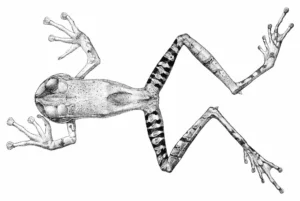

Due to a mostly herbivorous diet, tadpoles have very long tightly coiled intestines, that make up more than half of their body mass.

Plants contain cellulose, a compound that is very hard to digest. Because of this, plant matter needs to spend more time in the digestive system. This long intestinal tract gives tadpoles more time to break down the plant matter and absorb as many nutrients as possible.

The intestine takes up about half the space within the tadpole’s body and can be more than ten times longer than the tadpole itself.

Tadpoles Turn Into Frogs

After a few months to a few years (depending on the species) the tadpoles will go through a process known as metamorphosis, in which they will transform into juvenile frogs.

During metamorphosis, the thyroid gland secretes a growth hormone called thyroxine.

This hormone triggers the tadpoles to:

- Lose the gills, and develop lungs for breathing air

- Absorb the tail into the body

- Grow strong legs for moving on land

- Remodel other organs to form an adult frog

The tadpole’s beak is also shed, its denticles are reabsorbed and the mouth as a whole widens. In addition, the head structure also begins to change, leading to the development of a more defined jaw.

At this stage, the true teeth of many frog species also form.

In the mouth, secretory glands develop as does a tongue, which is muscular and can be quite long. It is also very sticky.

In addition, the digestive tract shortens dramatically, and the inner lining of the remaining intestine thickens, creating many folds in the process. These folds create a very large surface for the absorption of nutrients during digestion.

As the gut shrinks, a stomach is formed that secretes pepsin – an enzyme that is important for digesting proteins found in animal-based food.

Once metamorphosis fully is complete, tiny froglets will leave the water and live on land. These froglets are obligate carnivores and will grow into adult frogs over time.

Most Adult Frog Species Have Teeth on Their Upper Jaw

The tadpoles of most frog species develop true teeth as they go through metamorphosis and transform into adult frogs.

In general, most frog species have 2 types of teeth on the upper jaw: Maxillary Teeth and Vomerine Teeth.

These teeth are usually less than a millimeter long, so chances are, you would not notice them even if you opened a frog’s mouth.

Maxillary Teeth

Maxillary teeth refer to the teeth around the outer edge of the upper jaw (the maxilla), just like the teeth in our upper jaws. In frogs, these teeth look like little cones lining the edge of the upper jaw and are fairly uniform in size.

Since the maxillary teeth have a conical shape, they can not chew or tear apart food. They only help clutch onto the prey as the frog swallows it whole.

Vomerine Teeth

These are called “vomerine teeth” because they are found in the facial bone called the vomer. The vomerine teeth are usually organized in tiny clusters on the roof of the frog’s mouth, right behind the maxillary teeth.

Since these teeth are on the roof of the mouth, they cannot be seen unless the frog’s mouth is carefully examined. Even then, they are so tiny that you most likely won’t even notice them.

Like the maxillary teeth, the function of the vomerine teeth is to keep prey items in place while the frog swallows them whole.

Frog Teeth |

Human Teeth |

|

| Shape | Uniformly Conical | Flat (incisors), sharp (canines), rectangular (premolars & molars) |

| Function | Holding prey firmly in place | Biting, chewing, and grinding up food |

| Specialization | Do not specialize. All teeth have the same function | Specialize. Each type of tooth has a specific function |

| Replacement | Lifetime | Once |

Some Frog Species Have “Fangs”

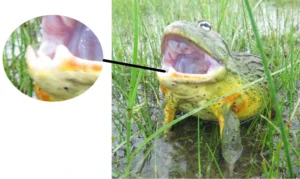

Some frog species such as those of the Limnonectes genus found in East and Southeast Asia have fang-like bony projections on the lower jaw.

The number of projections varies among different frog species, but 2 or 3 are common.

African bullfrogs (Pyxicephalus adspersus) are also notable for their bony “fang” projections. They have one small “fang” in the very center of the lower jaw, and two larger ones on either side.

These projections are not considered true teeth and are likely used in combat for access to prime mating sites and to protect themselves from predators

The Frog With True Teeth on Its Lower Jaw

The Guenther’s marsupial frog (Gastrotheca guentheri) is the only known frog with true teeth in its lower jaw, out of more than 7,500 species. Around 230 million years ago, the ancestors of modern frogs lost the teeth along their bottom jaws for good.

However, scientists believe the teeth of the Guenther’s marsupial frog re-evolved after being absent for over 200 million years.

It’s believed the re-evolution of teeth in the lower jaw may have been made easier by the fact that the frogs have teeth in their upper jaw so there was already a biochemical pathway for developing teeth after 200 million years, unlike, for example, birds.

Guenther’s marsupial frogs are native to Colombia and Ecuador. However, a living specimen has not been spotted in the wild since 1996, and some fear the species is already extinct.

Do Frogs Lose Their Teeth?

While humans only lose one set of teeth, frogs frequently lose teeth, which are then continuously replaced.

Sometimes, frogs will also replace functional teeth. The resorption of a functional tooth in amphibians is always related to the close presence of a growing replacement tooth.

When a replacement tooth is formed, it grows and, once fairly well-developed, its enamel organ generally contacts the lingual side of the functional tooth.

The contact induces the recruitment of osteoclasts, the cells that degrade bone. The functional tooth is then resorbed and the replacement tooth takes its place.

Toads Do Not Have Teeth

Unlike most frogs that have teeth for gripping prey, “true toads” in the family Bufonidae do not have teeth. Toad tadpoles do not develop any teeth as they go through metamorphosis and transform into adult toads.

Toads are opportunistic predators and rely on their sticky tounges to catch prey. When they spot an insect (or any other prey) they get just close enough to reach it with a quick flick of their long tongue.

After catching the prey, the tongue coats it with sticky saliva. The toad will then yank its tongue back, sometimes momentarily holding the prey with its jaws, and then swallowing it whole and alive.

Some toad species may use their front legs in order to eat larger prey. They grasp their food and push it into their mouths.

Toads do not need any teeth to catch, hold, or eat their prey.

Some Frogs May Bite Out of Self-Defense

Frogs are generally very docile creatures that will rarely intentionally bite a human. However, a frog may bite during aggressive feeding when it mistakes your hand or finger for food, when it feels threatened, or is being handled in a way that makes it uncomfortable.

A bite from the vast majority of frogs will usually be completely harmless. The frog’s tiny teeth are unlikely to penetrate your skin, or draw blood. Its teeth may feel like sandpaper brushing against your skin, but usually nothing more.

That being said, it’s important to note that some large frog species such as African bullfrogs (Pyxicephalus adspersus), and Pacman frogs (Ceratophrys) have relatively powerful jaws, and are capable of delivering a painful bite that can draw blood.

Pacman frogs have a bite force of about 30 newtons, which is equal to 3.06 KG or 6.74 lbs. This means they can bite several times their body weight.

Also, some frog species are generally more aggressive and are less reluctant to bite. Featured image credit: Bradley Davis (CC BY-NC 4.0)

Sources:

Davit-Beal, Tiphaine & Chisaka, Hideki & Delgado, Sidney & Sire, J-Y. (2007). Amphibian teeth: Current knowledge, unanswered questions, and some directions for future research. Biological reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. 82. 49-81. 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2006.00003.x.

Vera Candioti, Florencia & Altig, Ronald. (2010). A survey of shape variation in keratinized labial teeth of anuran larvae as related to phylogeny and ecology. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 101. 609 – 625. 10.1111/j.1095-8312.2010.01509.x.

Daniel J Paluh, Karina Riddell, Catherine M Early, Maggie M Hantak, Gregory FM Jongsma, Rachel M Keeffe, Fernanda Magalhães Silva, Stuart V Nielsen, María Camila Vallejo-Pareja, Edward L Stanley, David C Blackburn (2021) Rampant tooth loss across 200 million years of frog evolution eLife 10:e66926. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.66926

PRISCILLA STARRETT (1960). Descriptions of Tadpoles of Middle American Frogs. MISCELLANEOUS PUBLICATIONS MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN, NO. 110

Wiens, J.J. (2011), RE-EVOLUTION OF LOST MANDIBULAR TEETH IN FROGS AFTER MORE THAN 200 MILLION YEARS, AND RE-EVALUATING DOLLO’S LAW. Evolution, 65: 1283-1296. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01221.x

American Museum of Natural History. Toothless Predator. Accessed at: https://www.amnh.org/exhibitions/frog’s-a-chorus-of-colors/featured-frog-species/toothless-predator