Parental care is essential for the survival of offspring in many animal species. Usually when frogs breed both the males and females will leave the breeding site, leaving the eggs to fend for themselves. However, some species of frogs and toads provide care for their eggs and offspring.

Approximately 10–20% of frog species show some degree of parental care. In these species, parental care may include the formation of nests, attendance of eggs, brooding of eggs, transportation of tadpoles, protection of tadpoles, and feeding of tadpoles.

Most species only practice one, or a few of these forms of parental care.

For example, in many glass frog species (Centrolenidae), the mothers brood the eggs in the immediate hours after laying them. When eggs need long-term tending, fathers become single parents – brooding the eggs and guarding them against predators.

Male African bullfrogs (Pyxicephalus adspersus) protect their tadpoles from birds, snakes, and other animals trying to eat them (including other frogs). They also create paths for the tadpoles to move from drying up ponds to filled ponds.

In Darwin’s frogs (Rhinoderma darwinii), the males ‘swallow’ their tadpoles, and put them in their specialized vocal sacs – then release them as fully metamorphosed froglets.

There are even frogs that skip the tadpole stage to give birth to their babies as fully developed froglets that are readily capable of independent life.

Types of Parental Care in Frogs and Toads

Frogs and toads show a remarkable diversity of care, second only among vertebrates by the bony fishes (Osteichthyes).

The duration of parental care, the sex of the care provider, and the type of care are all uniquely diverse.

Parental care may last for weeks, or even several months in some species, whilst the parents defend, nurture and nourish their developing young.

Below are several types of parental care found in frogs and toads.

Formation of Nests

Many frog species create nest structures to lay their eggs in. These nests provide some sort of protection for the eggs.

1. Frothing of Water to Protect the Eggs

Some frog species such as the Fletcher’s frog (Platyplectrum fletcheri) of eastern Australia, deposit their eggs externally in mucus secretions within a water body.

They then beat the mucus into a froth with their hind legs, placing air bubbles between the eggs.

The froth nesting serves as a line of defense for the eggs, shielding them from the elements, and also from the sight of some predators.

Most notably, it serves as an effective protection against desiccation. The nest’s protective quality is further enhanced when the outer mucus dries to form a hard outer cast, reducing water loss by reflecting solar radiation and trapping moisture.

The protection is so effective that Fletcher’s frog eggs can survive and even continue developing for several days even if the water they were laid in dries up.

Although eggs in the outer layer of the nest structure dry more rapidly, the embryos in the center can be preserved long enough until additional rainfall replenishes the pond, helping to reduce larvae death.

2. Formation of Foam Nests to Protect the Eggs

Some frog species such as the Túngara frog (Engystomops pustulosus) found in Mexico, Central, and parts of South America – lay their eggs in a protective foam nest within a water body.

During the mating process, the female frogs produce an oviduct secretion. This secretion is then whipped up by the attending male’s hind legs to generate a floating foam nest in which the eggs are laid and fertilized.

When the tadpoles hatch, they will leave the nest and complete their development in the water.

Some tree frog species such as the gray foam-nest tree frog (Chiromantis xerampelina)of southern Africa and the Fourlined tree frog (Polypedates leucomystax) of Southeast Asia build their foam nests on vegetation or other objects hanging over the water’s surface.

When the eggs will hatch, tiny tadpoles will wriggle down the foamy secretion and pop into the water below.

These foam nests create perfect environmental conditions for the eggs while also protecting them from diseases and fungi.

3. Formation of Leaf Nests to Protect the Eggs

Some tree frog species such as the waxy monkey tree frog (Phyllomedusa sauvagii), of South America, and other frogs in the Phyllomedusa genus – lay their eggs in leaf nests.

These leaf nests are constructed above forest pools of standing water by folding the margin of the leaves (sometimes, more than one leaf).

To avoid desiccation of eggs, female waxy monkey tree frogs will lay empty gelatinous capsules in such a way that they surround the real eggs. These capsules provide extra fluid for the developing embryos and help to keep the eggs from drying out.

They also have adherent properties which helps the breeding pair in wrapping their nests with the leaf that they are laid on.

When the tadpoles, hatch they fall into the water, where they continue their development into adult frogs.

4. Formation of Mud Nests to Protect the Eggs

Some frog species such as the blacksmith tree frog ( Boana faber) found in part of South America protect their offspring by constructing mud nests at the water’s edge.

The female digs a small hole in the mud and builds a circular wall around the nest, which emerges above the surface of the water.

The inside wall is smoothened by the flattened webbed hands and the bottom is also leveled by the belly and hands.

This mud nest protects the eggs and early tadpoles from predators until they can defend themselves.

Heavy rains later on destroy the wall of the nest and the tadpoles go to the water where they complete their development.

Attendance And/or Brooding of Eggs

Some frog species such as the glass frogs (Centrolenidae), found in the humid forests of Central and South America lay their eggs on the underside or top of a leaf over a lake edge or a stream.

In many species, the females brood their eggs during the night the eggs are fertilized, and in almost a third of species, glass frog males remain with the newly laid eggs to defend them from predators until they hatch into tadpoles.

The male frog will also engage in hydric brooding, which is when the male will lay his body over the eggs to provide moisture and further protect the eggs from intruders like wasps.

Common coquis (Eleutherodactylus coqui) of Puerto Rico lay their eggs on plants away from water and even in abandoned bird nests.

Both males and females will fight off intruders from their nests by jumping, chasing, and sometimes biting.

The males are the primary caretakers of the eggs and provide moisture for the eggs by brooding them. This skin contact keeps the eggs moist – and during very dry periods, these frogs will leave and head to the water to gather more moisture for their eggs.

Common coquis have no tadpoles stage. Their eggs hatch into young fully developed froglets which are morphologically similar to the adults. This is known as ‘direct development.’

Carrying of Eggs on or in the Body

Some frog species carry their eggs on or in their body, to improve their chances of survival.

1. Carrying of Eggs Around the Legs

Midwife toads are found in most of Europe and northwestern Africa – get their name from the parental care they show for their eggs.

In these toads, the males carry the fertilized eggs on their backs, to protect them from predators present in the water.

When mating, the female releases an egg mass embedded in strings of jelly. The male then releases his sperm and inseminates the egg mass – then he pulls the egg mass so that he can wrap the strings around his waist and back legs.

When mating is complete, the female leaves, and the male carries the eggs with him on land until they are ready to hatch, in about 6 weeks.

The male will keep the eggs moist by lying up in damp places during the day, and going into the water if the eggs risk drying out. He will also produce a skin secretion that protects the eggs from infection.

2. Carrying of Eggs in Brood Pouches

Some frog species such as the horned marsupial frog (Gastrotheca cornuta), found in Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, and Panama – carry their eggs in back pouches.

When mating a female horned marsupial frog will lay a single egg and the male will fertilize it. He will then move it into a brood pouch on her back with his hind legs. The breeding pair will continue this cycle until all eggs are laid.

The eggs are carried in individual chambers in the female’s brood pouch for 60 – 80 days until they hatch into fully-developed froglets capable of independent life. Like the common coqui, these frogs have no free-living tadpole stage.

3. Carrying of Eggs in Cell-Like Pouches

Surinam Toads (Pipa pipa) are fully aquatic toads from the northern Amazon basin of South America. These toads are unique, in that the female gives “birth” to the young out of her back.

During the mating process, the female releases about 60 to 100 eggs, and the male fertilizes them and pushes the eggs onto her back, where they stick to her skin.

During the next few days, the skin continues to get thicker around each egg so that the eggs are embedded within her skin, forming an irregular honeycomb shape.

Soon after the female’s back is fully loaded with eggs, skin grows over the holes, protecting the developing offspring. During this time, the mother takes special care to protect herself and her young from predators and is rarely seen.

The embryos will develop to the tadpole stage inside of their egg pockets but will remain until they complete their development and become toadlets in about three to four months.

Once the eggs hatch, fully formed toadlets will pop out of the female’s back by squeezing out through the pore-like openings in her skin.

3. Carrying of Eggs in the Vocal Sac

Darwin’s frogs (Rhinoderma darwinii), are found in the forests of Chile and Argentina. These frogs have unique reproductive behavior in which they ‘swallow’ their tadpoles, and release them as fully metamorphosed froglets.

Female Darwin’s frogs lay there in moist leaf litter. The males, then fertilize the eggs externally and remain nearby.

Once the embryos have developed to a stage where they can wriggle inside of their eggs (about 20 days after the eggs are laid), the males swallow the embryos and put them in their specialized vocal sacs – where they hatch in about 3 days.

After hatching, the tadpoles will develop within the vocal sack for about 50 – 70 days. They are nourished by absorbing paternal nutrition produced by the wall of the sac, via the skin, and yolk from the egg.

As they develop, they will be able to consume parental nutritious secretions via the mouth and absorb them through their digestive system.

When the tadpoles have completed metamorphosis and transformed into miniature frogs, they will move from the male’s vocal sack, and hop out of the mouth.

Transporting of Tadpoles

Some frog species such as poison dart frogs (Dendrobatidae) found in the tropical forests of South and Central America, transport their tadpoles to pools of water where they can complete their development.

In many poison dart frog species, a female dart frog will lay her eggs on the forest floor, hidden beneath moist leaf litter, or on a moist leaf in some species. The eggs are in a cluster and have a jelly-like sac surrounding them.

After the eggs are laid, the male fertilizes the clutch. However, in some species, the male releases his sperm before the eggs are laid. The breeding pair will usually guard the eggs to make sure that they do not dry out.

After about 10 to 18 days the eggs will hatch into tadpoles. The tadpoles then wriggle carefully onto the back of an attending parent, where they are attached by a sticky mucus.

The parent then carries them to individual pools of water where they finish development. This is usually in pools of water that accumulate in epiphytic plants, such as bromeliads.

Once in the water, the tadpoles will swim around and eat algae and detritus, such as dead insects that fall into the water.

In some species, such as the strawberry poison dart frog (Oophaga pumilio), the females will also take care of the tadpoles by unfertilized eggs for them to eat until they turn into froglets.

Attendance of Tadpoles

Some frog species such as the African bullfrog (Pyxicephalus adspersus) protect and attend to their tadpoles to improve their chances of survival.

Male African bullfrogs guard their tadpoles against predators and, when necessary, insuring sufficient water is accessible to their tadpoles by digging channels that guide the tadpoles to larger bodies of water.

These guardian males have even been known to attack animals much larger than themselves to defend their offspring.

Feeding of Tadpoles

Some frog species such as the Giant ditch frog (Leptodactylus fallax) found on the Caribbean islands of Dominica and Montserrat – take care of their tadpoles by feeding them.

Giant ditch frogs lay their eggs in burrows around 50 cm (20 in) deep. During the mating process, the female releases a fluid, which the male makes into a foam with rapid paddles of its hind legs.

Once the foam nest is built, (which takes 9 to 14 hours) the male leaves the burrow, while the female remains beside the nest, inside the burrow.

Males remain outside the burrow, near the entrance, and defend the burrow if intruders approach. Females will also defend the nest if encroached.

After the tadpoles have hatched, the female lays up to as many as 10,000 – 25,000 unfertilized eggs (known as ” trophic eggs”) for the tadpoles to feed on.

While the tadpoles develop, which takes around 45 days, the female continuously renews the foam, rarely leaving the nest, apparently doing so only to feed.

When the tadpoles complete their development and undergo metamorphosis, 26 to 43 froglets emerge from the nest.

Giving Birth to Live Young

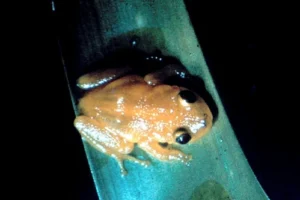

A few frog species such as the Golden coquí (Eleutherodactylus jasperi) do not lay eggs at all – instead, they give ‘birth’ to live young.

When these frogs mate, their eggs are fertilized internally and are retained within a uterus formed of fused portions of the oviducts.

The developing embryos are nourished by the egg yolks, and after a few weeks, the female will give ‘birth’ to tiny, fully developed froglets capable of independent life. This is known as “Ovoviviparity.”

Featured image credit: : MatiasG (CC BY-NC 4.0)

Sources:

Vági, B., Végvári, Z., Liker, A., Freckleton, R. P., Székely, T. (2019). Parental Care and The Evolution Of Terrestriality In Frogs. Proc. R. Soc. B., 1900(286), 20182737. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2018.2737

Cook, C. L., Ferguson, J. W. H., & Telford, S. R. (2001). Adaptive Male Parental Care in the Giant Bullfrog, Pyxicephalus adspersus. Journal of Herpetology, 35(2), 310–315. https://doi.org/10.2307/1566122

Ana L. Salgado, Juan M. Guayasamin “Parental Care and Reproductive Behavior of the Minute Dappled Glassfrog (Centrolenidae: Centrolene peristictum),” South American Journal of Herpetology, 13(3), 211-219, (30 September 2018)

Agar, W.E. (1909), The Nesting Habits of the Tree-Frog Phyllomedusa sauragii. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, 79: 893-897. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7998.1910.tb06980.x

Gould, John & Valdez, Jose & Clulow, John & Clulow, Simon. (2021). Left High and Dry: Froth Nesting Allows Eggs of the Anuran Amphibian to Complete Embryogenesis in the Absence of Free-Standing Water. Ichthyology & Herpetology. 109. 537-544. 10.1643/h2020142.

Dalgetty, L. C., Kennedy, M. W. (2010). Building a Home From Foam—túngara Frog Foam Nest Architecture And Three-phase Construction Process. Biol. Lett., 3(6), 293-296. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2009.0934

Gould, J. (2021, March 03). Froth Nesting. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/7703

O’Connell, Lauren. (2020). Frank Beach Award Winner: Lessons from poison frogs on ecological drivers of behavioral diversification. Hormones and behavior. 126. 104869. 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2020.104869.